EFPMC: A Monte Carlo implementation with the EFP Method

When I was apart of a theoretical group, we pride ourselves on being on the frontier of chemistry studying interactions between matter in it’s purest form – mathematically (and I guess programmatically).

However – we also needed to get funding so we had to tackle use cases to apply our theory. One of those use cases involved understanding the effect of cofactors on co-crystal formulations for active pharmaceutical ingredients. However, performing an exhaustive experimental screening is experimentally expensive. Thus, there is a need for a tool that is relatively accurate yet computationally cost effective for the virtual screening of drugs based on changes in functional group interaction energies in order to approximate free energy changes. My particular contribution was implementing of the Monte-Carlo method and perform some simple benchmarking studies for this particular use case.

Monte-Carlo Sampling

Whelp.

Here goes the technical implementation of a Monte-Carlo integration over configuration space using the effective fragment potential (EFP) method as a description for a chemical system. Using the effective fragment potential method, is possible to calculate energetic properties of any substance of a system of \(N\) interacting EFP fragments:

\[E^{EFP}=E_{coul}+E_{ind}+E_{exch}+E_{disp}+(E_{CT})\]In order to explore the configurational space, random sampling of points are obtained through moving each EFP fragments from an initial configuration in succession:

\[x = x + \alpha\xi_{x}\] \[y = y + \alpha\xi_{y}\] \[z = z + \alpha\xi_{z}\] \[a = a + \alpha\xi_{a}\] \[b = b + \alpha\xi_{b}\] \[c = c + \alpha\xi_{c}\]where \(\alpha\) is the maximum allowed displacement, and \(\xi_{x}\), \(\xi_{y}\), \(\xi_{z}\), \(\xi_{a}\), \(\xi_{b}\), \(\xi_{c}\) are random numbers between (-1) and 1. \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) refer to the Cartesian coordinates for the center of mass of a fragment. \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) refer the fragment’s Euler angles. The change in energy of the system \(\Delta E\) following the move is calculated. If \(\Delta E > 0\), then the move is evaluated against probability of \(exp(\Delta E/kT))\) where a random number \(\xi_{4}\) between 0 and 1 is evaluated against \(exp(\Delta E/kT))\). If \(\xi_{4}\ < exp(\Delta E/kT))\), then the system configuration is accepted despite \(\Delta E > 0\). However if \(\xi_{4}\ > exp(\Delta E/kT))\), then the move is rejected and the system is returned to its prior configuration.

Technical Implementation

The general EFP method has been implemented as a library API called libefp. The libefp library and efpmd integration program are written in fully portable standard C language and parallelized using OpenMP. Here we describe some brief additional functions to efpmd program that serves as the integrator for a Monte-Carlo simulation with the EFP method. You can find a branch of the efpmd-mc implementation at my branch libefp_Terri.

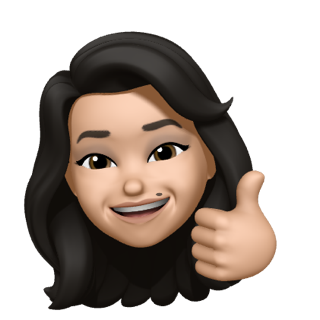

Here is a general scheme of my modification to the source code:

In order to perform Monte-Carlo using the EFP method, a new subroutine sim_mc() was introduced and linked to the efpmd program. The simulation configurations for performing a EFP-MC calculations, involve the run_type flag introduced as ‘run_type mc’ and max_step and temp general parameters for the simulation. Similarly to other run_types in efpmd, sim_mc() is initialized in its own header file (mc.h) and declared in mc.c, both located in the ~/efpmd/src/ directory. sim_mc includes/calls on other functions in the efpmd program through header files math.h, common.h, and rand.h. Running a EFP-MC related parameters that control the step size are:

- Max Displacement Step Size: dismag_threshold [default = 0.05]

- Update Displacement Step Size: dismag_modifier [default = 0.95]

- Frequency of Updating Displacement: dismag_modify_steps [default = 100]

System information is parsed and stored in struct mc_state in the void mc_create. It is within mc_state that the initial configuration for the original configuration is accessible. Mc_state also contains a dynamic array for proposed configuration x_prop that is updated at each step of the simulation. Enum mc_init is the function that allocates the memory for mc_state, along with initializing the Monte-Carlo step counter ‘step’, the initial accepted step n_accept and rejected steps n_reject.

Accessory functions such mc_set_func() and mc_set_user_data() are provided in order to transfer data structures and simulation configuration information populated within the initial main() function in main.c to data structures within sim_mc(). Sim_mc which is able to communicate with the library function libefp through subroutine check_fail() that passes the atomic coordinate and point charge coordinate information for each fragment.

When running a Monte-Carlo simulation, sim_mc calls on mc_step() multiple times in a while loop for the number of max_steps the user specifies. At each step, mc_rand() is called to randomize the center of mass (COM) of one fragment in the simulation. The energy of the state is obtained through compute_efp() that calls on libefp function efp_compute() through compute_energy(). With each Monte-Carlo step, evaluation of the move is done through check_acceptance(). If the move is accepted, the proposed coordinates stored in struct x_prop will be copied to struct x. Else, another step is taken and the proposed configuration is evaluated.

S22 Dataset

In order to examine the robust of the Monte-Carlo code it was necessary to examine the ability of the program to sample different phase space of different systems. Previous efp parameters generated for the S22 dataset are readily available through the libefp package. The Coulomb part of these parameters was obtained with analytic Stone DMA, using HF/6-31+G(d)(42-44) and HF/6-31G(d) for nonaromatic and aromatic molecules, respectively. The rest of the potential, that is, static and dynamic polarizability tensors, wave function, Fock matrix, etc., were obtained with the 6-311++G(3df,2p) basis set.(44-46) To account for the short-range charge-penetration effects, overlap-based electrostatic and dispersion screenings as well as Gaussian-like polarization screening were employed.

Finding the potential minima from an optimized geometry

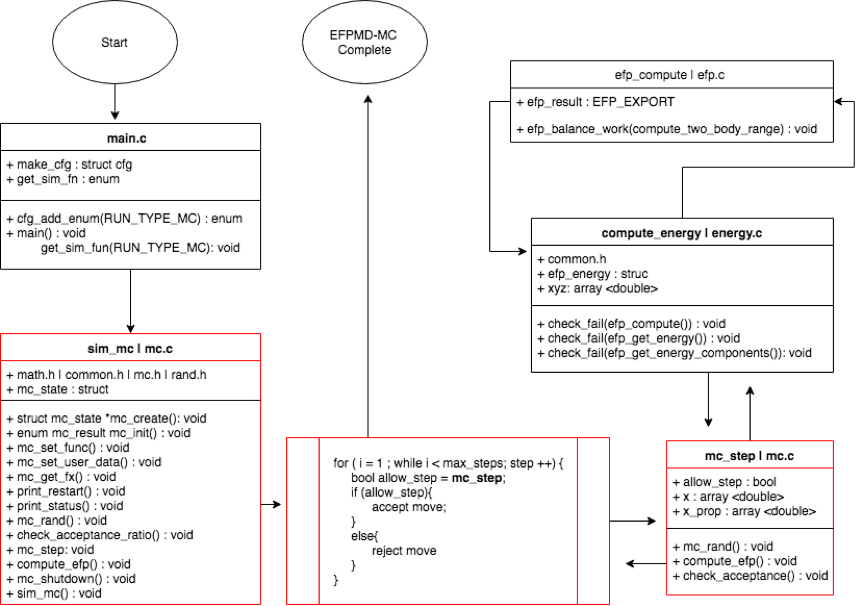

S22 is a data set of dimer complexes are divided into three subgroups: (i) hydrogen bonded complexes; (ii) complexes with predominant dispersion stabilization; (iii) mixed complexes in which electrostatic and dispersion contributions that are similar in magnitude. Of the 22 complexes, 6 of the dimers were optimized at the CCSD(T) level in cc-pVTZ and cc-pVQZ basis sets, and so were selected as initial configurations.

Each configuration served as the initial step, for an EFP-MC simulation with 10,000. Each simulation was run with a displacement maximum threshold of 0.05 and displacement modifier of 0.95 utilized ever 500 steps. After the simulation, the configuration with the lowest energy was obtained for each dimer and geometry optimized using efpmd. The geometry optimized structure following Monte-Carlo simulation (EFP MC_Opt) was then compared against a EFP geometry optimized structure (EFP Opt) and the initial CCSD(T) structure itself (CCSD Opt).

| Complex | EFP MC | EFP MC_Opt | EFP Opt | CCSD Opt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ammonia | -4.72 | -5.37 | -5.37 | -3.17 |

| ethene | -2.70 | -3.16 | -3.16 | -1.51 |

| ethene-ethyne | -1.92 | -2.32 | -2.32 | -1.53 |

| formic acid | -980.38 | -16.65 | -16.65 | -18.61 |

| methane | -0.92 | -1.04 | -1.04 | -0.53 |

| water | -5.90 | -5.99 | -5.99 | -5.02 |

Using the Monte-Carlo method with EFP would likely find a non-equilibrium configuration close to one of the local EFP minima. Optimization of that non-equilibrium configuration, would result in finding this local EFP minimum. EFP-MC values for the lowest energy minima using a geometry optimized EFP-MC (EFP MC_Opt), EFP-MC (EFP MC), EFP optimized structure (EFP Opt), and CCSD(T) initial reference structure (CCSD Opt).

Finding Potential Minima From Non-equilibrium Geometries Rather than focus on finding a single minima/stationary point, it was important to see if the Monte-Carlo algorithm in conjunction with EFP would be able to explore and find local minima beyond the minima obtained through geometry optimization. Thus, the EFP parameters for 6 dimer complex from the S22 dataset were once more utilized. However, the initial configurations were not the obtained CCSD(T) geometry optimized structures, but were randomly placed twice the original intermolecular distance apart. These geometries were obtained from the S22 non-equilibrium geometries . For each dimer complex, a Monte-Carlo simulation was run for 10,000 steps, displacement maximum threshold of 0.05 and displacement modifier of 0.95 utilized ever 500 steps. After the simulation, the configuration with the lowest energy was obtained for each dimer and geometry optimized using efpmd. The geometry optimized structure following Monte-Carlo simulation was then compared against a reference efpmd geometry optimized starting from the 10 angstrom apart dimer structure.

| Complex | EFP MC_Opt | EFP Opt | CCSD Opt |

|---|---|---|---|

| ammonia | - | -1.67 | -0.36 |

| ethene | -1.86 | -3.15 | -0.03 |

| ethene-ethyne | -1.55 | -1.54 | -0.15 |

| formic acid | -16.61 | -16.61 | -3.63 |

| methane | -1.03 | -1.03 | -0.01 |

| water | -7.07 | -5.71 | -0.96 |

In the Table above we see that EFP using Monte-Carlo was able to obtain different minima (EFP MC_Opt vs. EFP Opt) rather than just falling into the original geometry optimized minima presented - implying that the system was able to overcome energy barriers and explore different potential energy minima. With Ammonia, we were not able to obtain a optimizable local minima using the same simulation with Monte-Carlo and so is not provided in this table. The ability to EFP-MC explore potential minima was encouraging and thus we attempted to find local stationary points on well established potential energy surfaces of a water dimer.

Water Dimer Local Minima

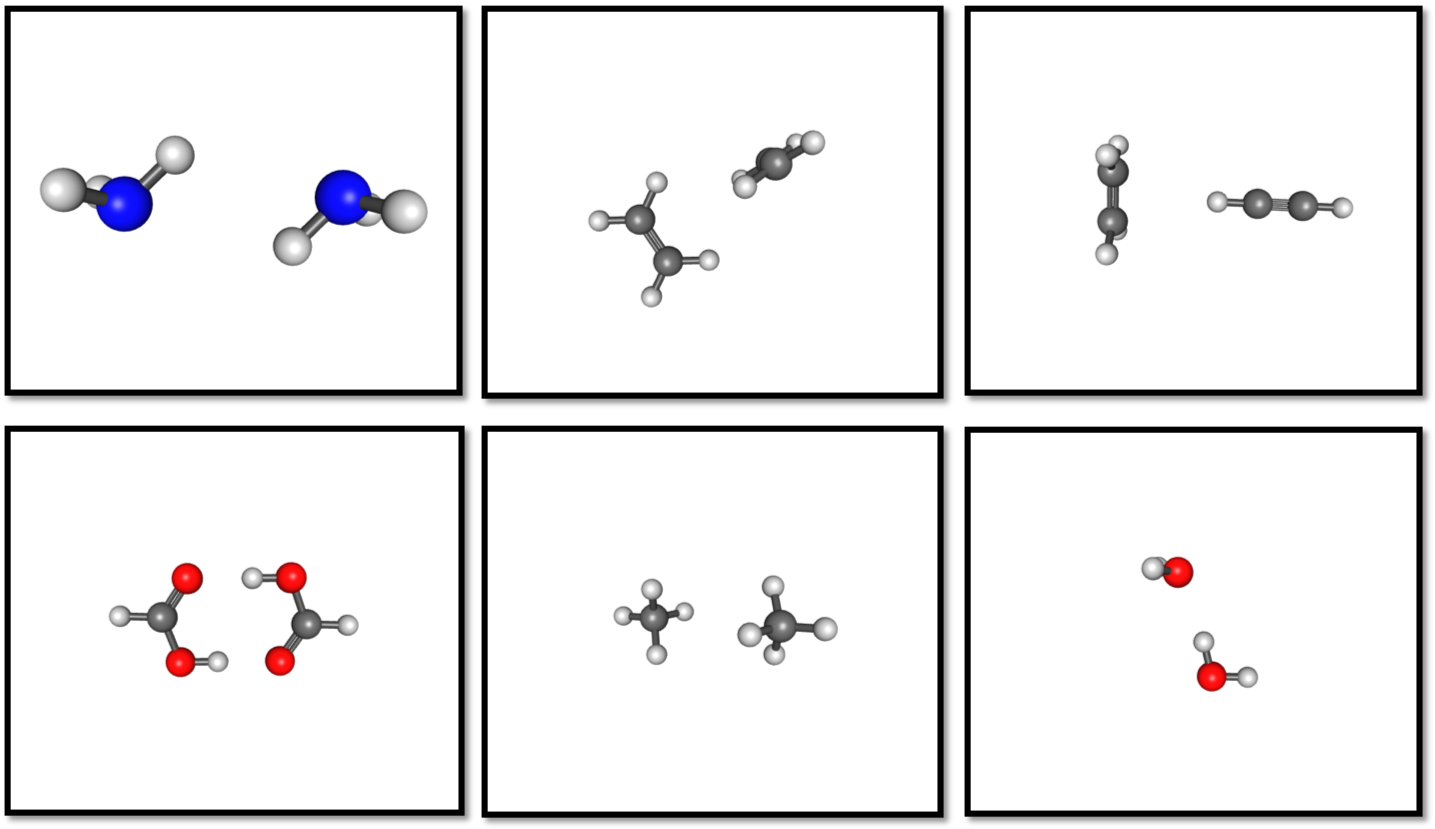

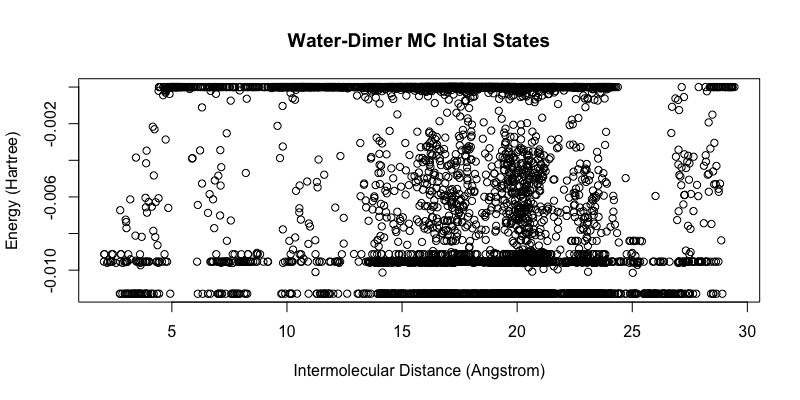

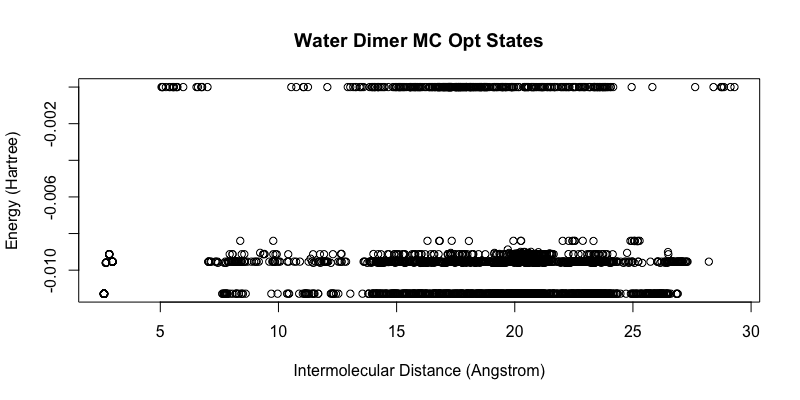

Here, the water dimer configuration obtained from S22 non-equilibrium dimer configuration served as the initial step. The simulation was ran with 10,000 steps using efpmd with a displacement maximum threshold of 0.05 and displacement modifier of 0.95 utilized ever 500 steps with periodic conditions of 10 Angstrom. After the simulation, each Monte-Carlo step was then geometry optimized using efpmd. The initial Monte-Carlo obtained configurations are depicted in the figure below as energetic states distinguishable by intermolecular distance (without periodic boundary conditions applied). Although, the obtained energies are obtained with periodic boundary conditions, it was easier to distinguish individual states with respect to their coordinates without PBC in order to ‘smear’ the density of points and see energy groupings.

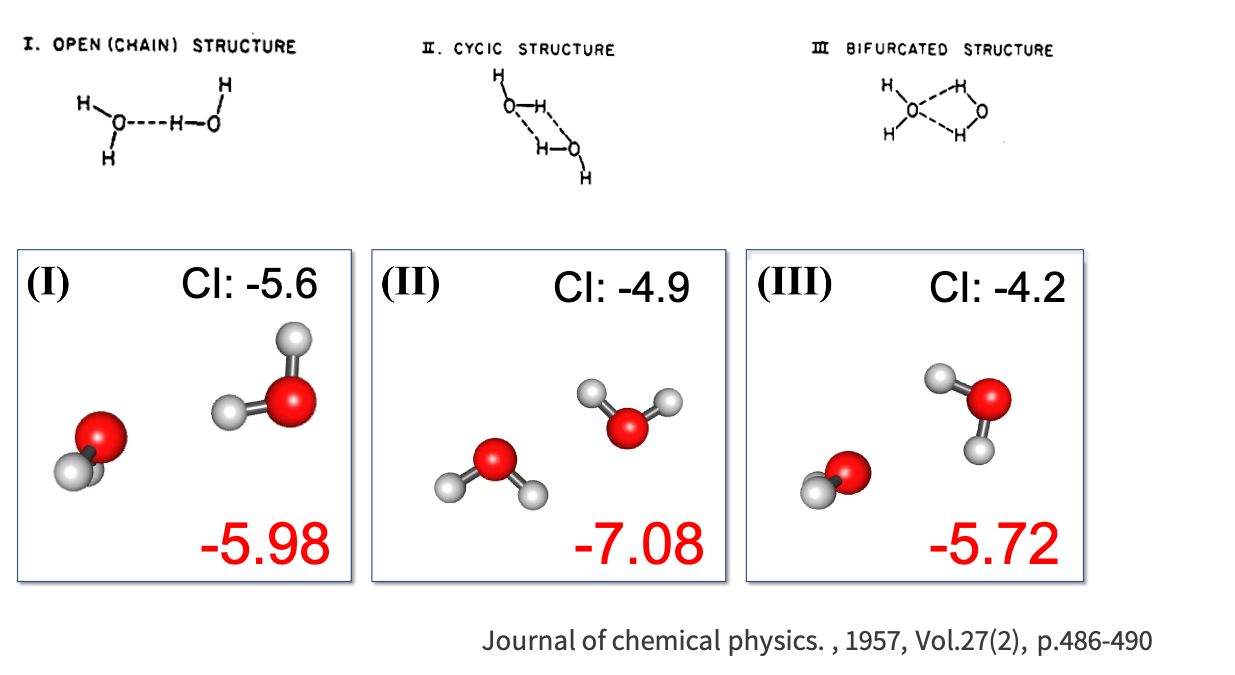

When looking at the obtained energy states from the initial configurations, we see a reduction in the number configurations and it is easy to ascertain that there are approximately 3 ‘lines’ or minima of a water dimer. From these configurations, the 3 final configurations found correspond to the linear (I), cyclic (II), and bifurcated (III) CI potential minima by Matsoka et. all. EFP energies and CI literature energies are reported as:

| Configuration | EFP | CI |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | -5.98 | -5.6 |

| Cyclic | -7.08 | -4.9 |

| Bifurcated | -5.72 | -4.2 |

This is a promising result that EFP is able to minimally obtain previously cited local minimum obtained using CI methods.

Conclusions

The theoretical and technical implementation of the Monte-Carlo method in the libefp package is reported. Benchmark studies on the ability of EFP-MC to appropriately phase-space sample relative to both CCSD(T) geometry optimized equilibrium and non-equilibrium geometries on the S22 dataset are reported. The configurations obtained and presented here are in good agreement with those obtained using accurate first principles methods as demonstrated by finding the linear, cyclic, and bifurcated structures with comparable energetics. These results demonstrate EFP-MC as method for obtaining local and global minima on a potential energy surface of a molecular model. Thus, this work serves as a promising means to perform co-crystal screening with EFP-MC as a sophisticated alternative to docking methods.